“I favor the policy of economy, not because I wish to save money, but because I wish to save people.”

— Calvin Coolidge, 1925

A Stupendous Feat

Today, American presidents and Congress struggle to control the federal budget. Deficits, not surpluses, have become the rule for the federal household. Crises come and go, but the debts they create stay with us. Indeed, the spending we commit to during crises, we often continue after those crises. During wars, the government gets bigger. Coming out of war, a president will sometimes manage to team up with Congress to cut government–some. That's what President Harry Truman managed, for example. Once peacetime comes, however, presidents and Congress seem to have a tough time cutting further.

The presidents after World War I confronted just such challenges. The national debt from inducting and mobilizing several million soldiers overnight, and then prosecuting the war proved enormous. Yet unlike leaders today, Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge determined to tackle the debt post-Crisis. Elected in 1920, President Harding took the first steps toward achieving the goal.

But in the 1920s budget saga, it is Calvin Coolidge who stands out. Coolidge, who became president upon the sudden death of Harding in the summer of 1923, took up the budget cutting campaign with the same determination that other presidents prosecute foreign wars. The result was stunning. Coolidge, a peacetime president, balanced the budget every year of his presidency, an accomplishment managed by no president since. By the end of the Coolidge presidency, the federal debt was down by one-third, manageable. Another important achievement: Coolidge left office with a federal government smaller than when he arrived. Perhaps most important: thinking of the future, Coolidge repeatedly blocked programs that would have expanded government spending after his tenure. All these are rare achievements for a peacetime president.

Showing exactly how Coolidge managed these stupendous feats is the work of this website. The tools included a strong party platform, a special budget law, and a commitment to restoring prosperity through policy, including dramatic tax cuts. To find out more, check out the material below. We know that in this 1920s budget story of a century ago you'll find lessons that can serve America today.

I. A Post-Crisis Challenge

World War I cost the U.S. some 100,000 soldiers their lives and billions of dollars. After the Armistice, it was clear America was set to struggle with the war’s consequences: record-high federal debt and high taxes. There was also rampant inflation, followed by a severe but short business slump. Households found that they couldn’t afford basics such as bread, or coal to heat their houses. Labor strikes plagued large industries, such as rail, steel, and coal. A new kind of strike, a strike of public sector workers, was becoming common. In Governor Coolidge’s own Boston, the police mounted a strike. Coolidge, in fact, rose to national prominence when he drew a line in the sand regarding such a strike, stating “[t]here is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”

Businesses too went on strike–“capital strike,” as it was called–saying they could not recover, grow, or hire in such an environment. To top it all, the debt from World War I made further spending by the federal government impossible. The United States had to cut.

The tools for handling the budget crisis were missing: for example, the Federal government lacked a functioning budget process. The President had no way of overseeing the budget in its entirety, but had to decide ad hoc which spending proposal from Congress to support, and which to veto.

II. A Strong and Detailed Platform

These days voters tend to focus on the qualities of candidates, debating the personal qualities of candidates rather than party plans for policy. In 1920, both parties put considerable effort into their platforms, including plans to curtail war-scale national spending and slash wartime debts. Both parties promised budget reform. Democrats in 1920 promised voters that they would reform the budget process: “we favor the creation of an effective budget system” the Democratic Platform read. The Republican Party also pledged to reform the budget process. The Grand Old Party committed to “a return to normalcy.” This meant getting that new budget law, getting spending under control, paying down the record-high federal debt, and lightening what it termed the “staggering” tax burden on the greatest supplier of jobs in the country: business. The Republicans also argued that “normalcy” meant returning certain government assets, such as oil reserves, to the private sector, which would manage them better. They argued the government could not afford big pensions for veterans and promised instead an economy that would help veterans get back to “normal” in their own lives. For voters, the 1920 choice boiled down to which party would try harder to restore America. The voters chose the Republicans. Come November 1920, the Republicans, Senator Warren Gamaliel Harding of Ohio and Governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts, carried 37 of 48 states. Republicans carried both Houses of Congress, too. Both Harding and Coolidge, and the country, recognized that any new leadership must make good on its promises.

III. A New Law

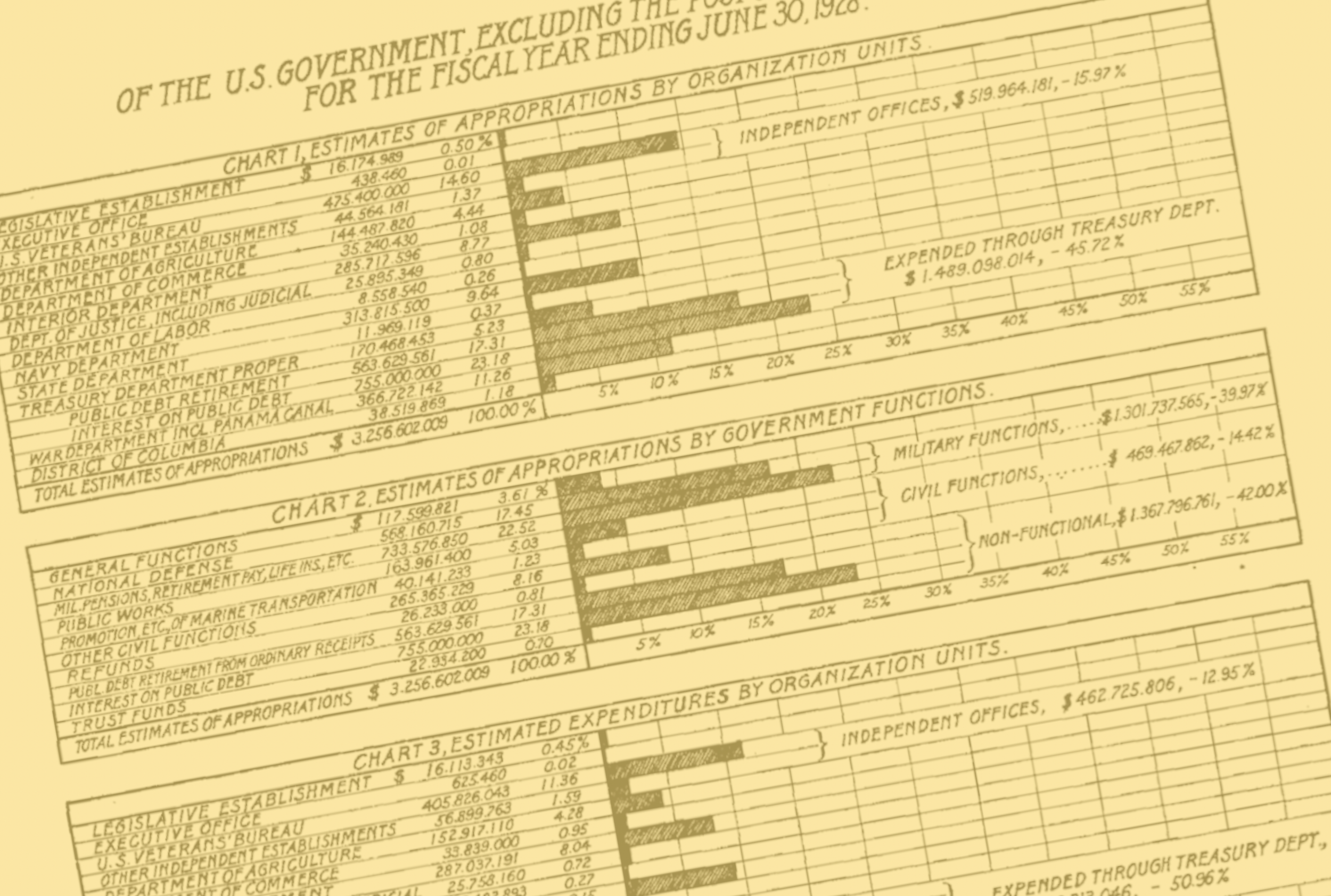

In 1921, President Harding took the key first step toward Normalcy. President Wilson had vetoed legislation to reform the budget in 1920. Now, the new leaders took up a version of the same legislation and pushed it through Congress. Harding signed the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 into law. The new law required the president to submit to Congress a budget proposal at the start of each regular session. Preparing a budget requires an immense amount of data and organization, and, in the days before computers, many workers and months. To aid the president in preparing budget proposals, the Act also established the Budget Bureau, a kind of personal research office. The Budget Bureau, a version of what we today call the Office of Management and Budget, compiled data for the president. The 1921 Budget and Accounting Act also established the General Accounting Office, known today as the Government Accountability Office. The GAO, independent of the executive, audited government accounts and records, previously handled by departmental auditors. Overall, though, the 1921 Act significantly increased the role of the executive branch in the budgeting process.

IV. Taxes and the Business of America

Federal budgeting alone can’t engender prosperity. The business environment had to be certain enough for businesses to want to create jobs. Businesses have to have the certainty to know they can keep a good share of what they make. But in the early 1920s, businesses could not be sure. The top rate on the individual income tax in 1920 was 73%. Yet worse, from the point of view of many, was the tax on capital gains, the tax levied when you buy or sell a stock. Statute at the time was so murky that no one could even establish what the rate on capital gains was. In 1921, President Harding sought to reestablish certainty by making clear taxes were only going in one direction: down. He led Congress in passage of a new tax law that made business life easier by clearly setting the capital gains tax at 12.5%. The 1921 Tax Act also dropped the top income tax rate to 58%–still high, but a start. The Harding Administration and Congress planned yet further rate cuts, but when the Republican majority diminished in the 1922 midterms, the prospects for dramatic cuts dimmed. And in August, 1923, a sudden tragedy threatened to abort the program for “normalcy.” While traveling in the West, President Harding passed away.

V. Spotlight on a New President

The challenges for the new man in the White House were numerous. For one, scandals involving the late president’s appointees were emerging. The record of Harding’s allies and Harding’s failure to oversee those allies were besmirching the very principles upon which Harding, Coolidge, and their party had won election in 1920.

The Republicans, for example, had advocated handing government oil reserves to private hands. But by 1923 it was becoming clear that in the case of some energy reserves, friends and acquaintances of Harding Cabinet members had received sweetheart deals for government oil contracts. The scandal, known as “Teapot Dome,” after the location of the oil reserves, was a serious one. The Republicans had opposed the creation of large permanent pensions for veterans, on the principle that it would set a dangerous trend of prohibitive long-term obligations the nation couldn’t afford. Now Harding’s compromise plan for veterans–not payments, but hospitals to care for them–also looked bad. It turned out that those who built the hospitals received kickbacks. Such scandals hurt not only the memory of Harding but also Coolidge’s prospects for free market reform. If privatizing energy was corrupt, then the case for government-controlled energy looked better. If veteran hospitals were corrupt, then veterans had a better case for direct payments, what we today would call “entitlements.”

Another challenge to Coolidge was that he took office in the second half of the presidential term. By the time Coolidge set up shop in the White House–autumn, 1923–only a year remained before the next presidential election. Perhaps, the press speculated, this accidental president, as some labeled him, would be just a Lame Duck. But Coolidge determined to fulfill the 1920 platform: “[Harding] is gone. We remain. It is our duty, under the inspiration of his example, to take up the burdens which he was permitted to lay down, and to develop and support the wise principles of government which he represented.” Coolidge would do more than emulate Harding’s policies, he would pursue the aims to “perfection.” Though America did not yet know Coolidge well, the country realized Coolidge had some key qualifications for his new job: a career of budgeting and lawmaking in a prominent state, Massachusetts. Soon America saw that Coolidge was serious.

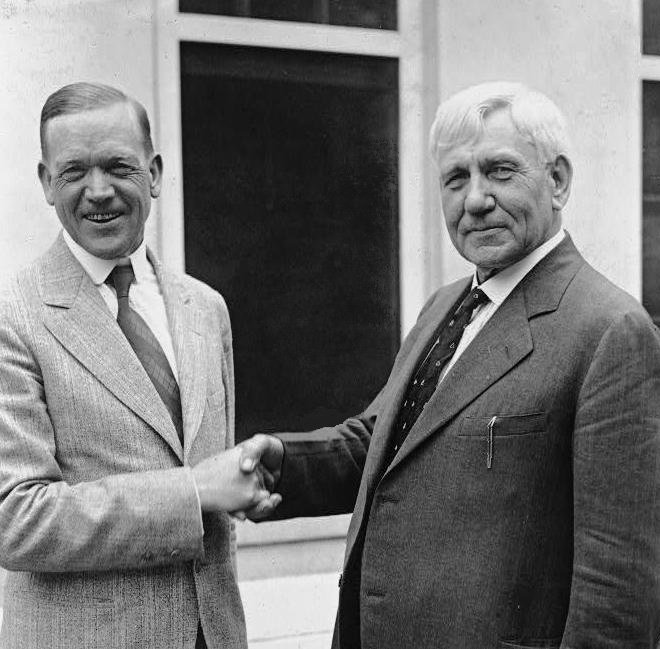

VI. A Key Ally

Coolidge could have switched out some members of the old Harding cabinet, and Attorney General Harry Daugherty did eventually resign in the cleanup of the Teapot Dome Scandal. But Coolidge knew that if he was to deliver on the agenda he and Harding had promised, he must keep a key ally, Harding’s Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon. Mellon was one of the greatest businessmen of the era, something like a combination of Warren Buffett and Fred Smith of FedEx in one. Through building his own companies, Mellon had learned a crucial skill: managing debt. Mellon offered to resign. Coolidge responded by insisting Mellon stay and lead both the drive to reduce the debt and the drive to rationalize taxes. Effective presidents know how to delegate. Coolidge delegated to Mellon the development of plans to cut both the nation’s debt and tax burdens.

VII. Scientific Taxation

It was in the tax area that Mellon made his greatest mark. His work started with a premise: to balance the budget, the government needed revenues. Mellon had learned from decades in business that, as he put it, “[i]f a price is fixed too high, sales drop off and with them profits,” and “if a price is fixed too low, sales may increase, but again profits decline.” The rule at Mellon’s railroads was that railroad owners should charge “what the traffic will bear.” The same principles, Mellon said, could explain the disappointing flow of tax revenues. Mellon was so determined that he even wrote a book, Taxation: The People’s Business, to explain his thoughts. “Does anyone question that Mr. Ford has made more money by reducing the price of his car and increasing sales than he would have made by maintaining a high price and a greater profit per car, but selling less cars? The Government is just a business, and can and should be run on business principles.” In Mellon’s theory, lower tax rates would lead to greater tax revenues than predicted because the increase in incomes spurred by economic growth would make up at least some of the money lost when rates dropped. Mellon and Coolidge pushed through passage of a second tax act. The Revenue Act of 1924 dropped the top income tax rate to 46 percent–not low enough, Mellon and Coolidge made clear, but still an improvement.

Taxation: The People’s Business by Andrew W. Mellon, 1924.

VIII. The Challenge of Farms

As today, however, there were plenty of groups making a case that they needed support immediately. During World War I, and at Washington’s demand, American farmers expanded production to feed our soldiers and to export to Europe. Prices and profit exploded. So promising seemed farming that many farmers purchased more land to expand their operations. After the war, prices for agricultural commodities dropped precipitously. Farms were suddenly struggling to survive.

Farmers and their supporters wanted a system that guaranteed farming’s profitability. They wanted Washington to stop the boom-bust cycle. Senator Charles McNary of Oregon and Congressman Gilbert Haugen of Iowa mounted a national campaign for a new federal regime to give struggling farmers of any era relief. The McNary-Haugen bill proposed to create a Federal Farm Board that would sustain prices for certain commodities at pre-war levels and manage markets by buying surpluses from farmers. Under the plan, this new Board would calculate and then charge farmers an “equalization fee” for their losses.

IX. The Challenge of Veterans’ Relief

No group seemed more compelling than veterans. Many of the veterans had trouble finding work; some 200,000 had been wounded, many disabled for the rest of their lives. The very least, the veterans said, the government could do was give them a pension, or “bonus.” There was no national pension program like Social Security in those days. The veterans lobbied for a veteran pension from Washington. By 1923, economic recovery was well underway. Mellon’s Treasury was indeed paying down the national debt. The veterans argued the moment had come for Washington to reward them for service by making pensions for World War I vets the law of the land.

X. Coolidge Says “No”

Turning down compelling groups like farmers or vets put the new president to the test. Vetoing legislation to help suffering groups makes a president look inhumane. Yet Coolidge believed that a balanced budget and restrained government did the most for America.

Coolidge vetoed McNary-Haugen twice. He also vetoed two bills for veteran pensions and bonuses in 1924, the latter of which Congress overrode. In all, Coolidge vetoed 50 pieces of legislation. Vetoing is an art. Coolidge found success in meeting his goals when he favored a certain form of veto, the pocket veto, by which a president, during Congressional recess, simply allows a bill to die. But even when his vetoes were overridden, he was satisfied. A veto sent an important signal that he was serious about his aims.

Coolidge took care to explain the reason for his vetoes to the electorate. In the message accompanying his May 1924 veto of a bill that gave pensions to vets and families, he said: “The desire to do justice to pensioners, however great their merit, must be attended by some solicitude to do justice to taxpayers. The advantage of a class cannot be greater than the welfare of the Nation.” Two weeks later, Coolidge vetoed for the same reasons a similar bill that would have increased bonuses already pledged to World War I veterans and their families. Coolidge went beyond the balance books in this veto message, writing:

Those who do seek a money recompense for the most part, of course, prefer an immediate cash payment. We must either abandon our theory of patriotism or abandon this bill…. Service to our country in time of war means sacrifice. It is for that reason alone that we honor and revere it.

President Coolidge resisting lawmakers’ demands. See if you can spot Senator William Borah, and Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover. (Artist, Paul Rivoche)

XI. Coolidge and Defense

Today lawmakers must confront a budget replete with entitlements: Medicare, Medicaid, forms of welfare, and standard benefits to veterans. Budgets today differ from those of Coolidge’s era. To compare current and 1920s budgets, click here.

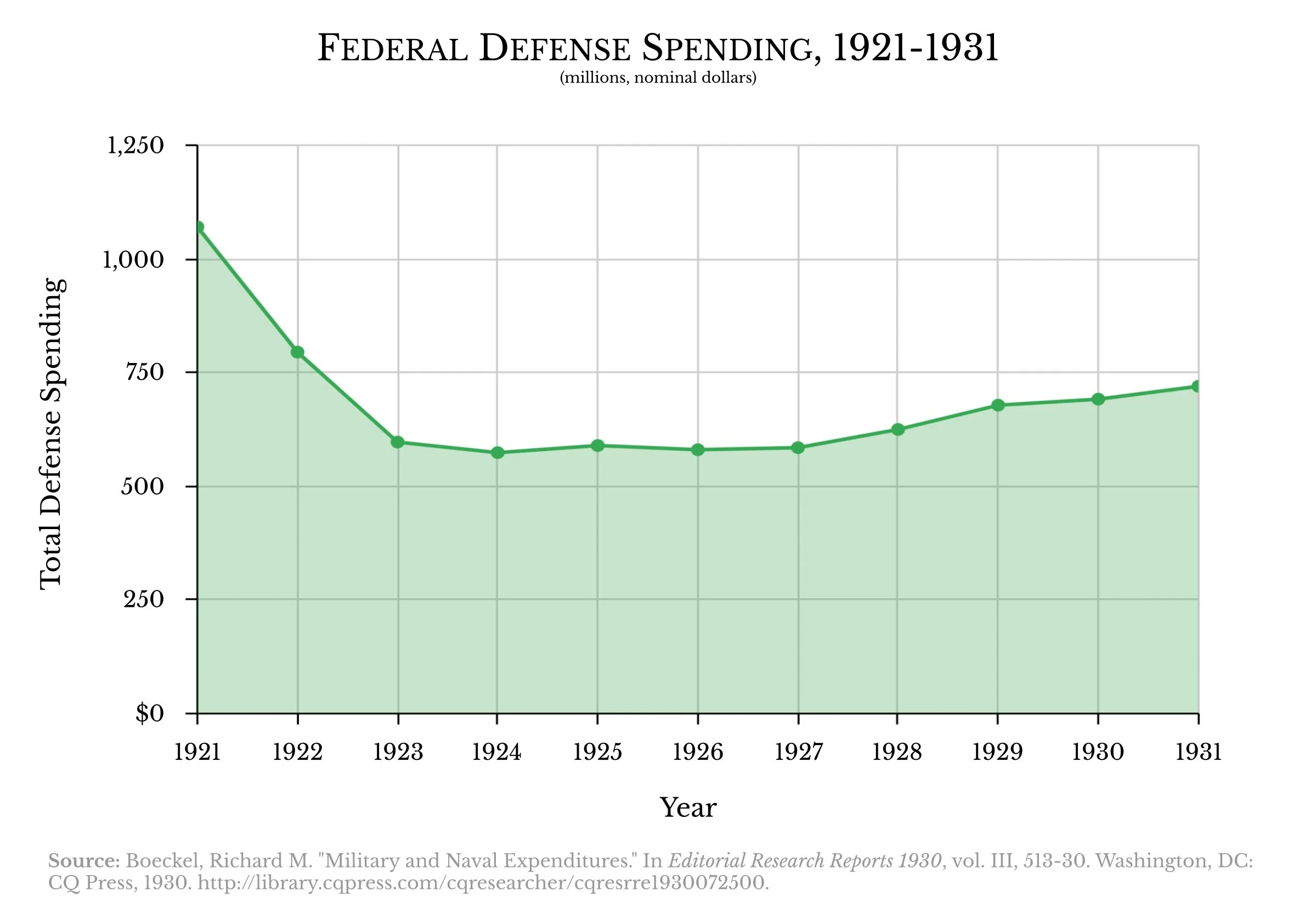

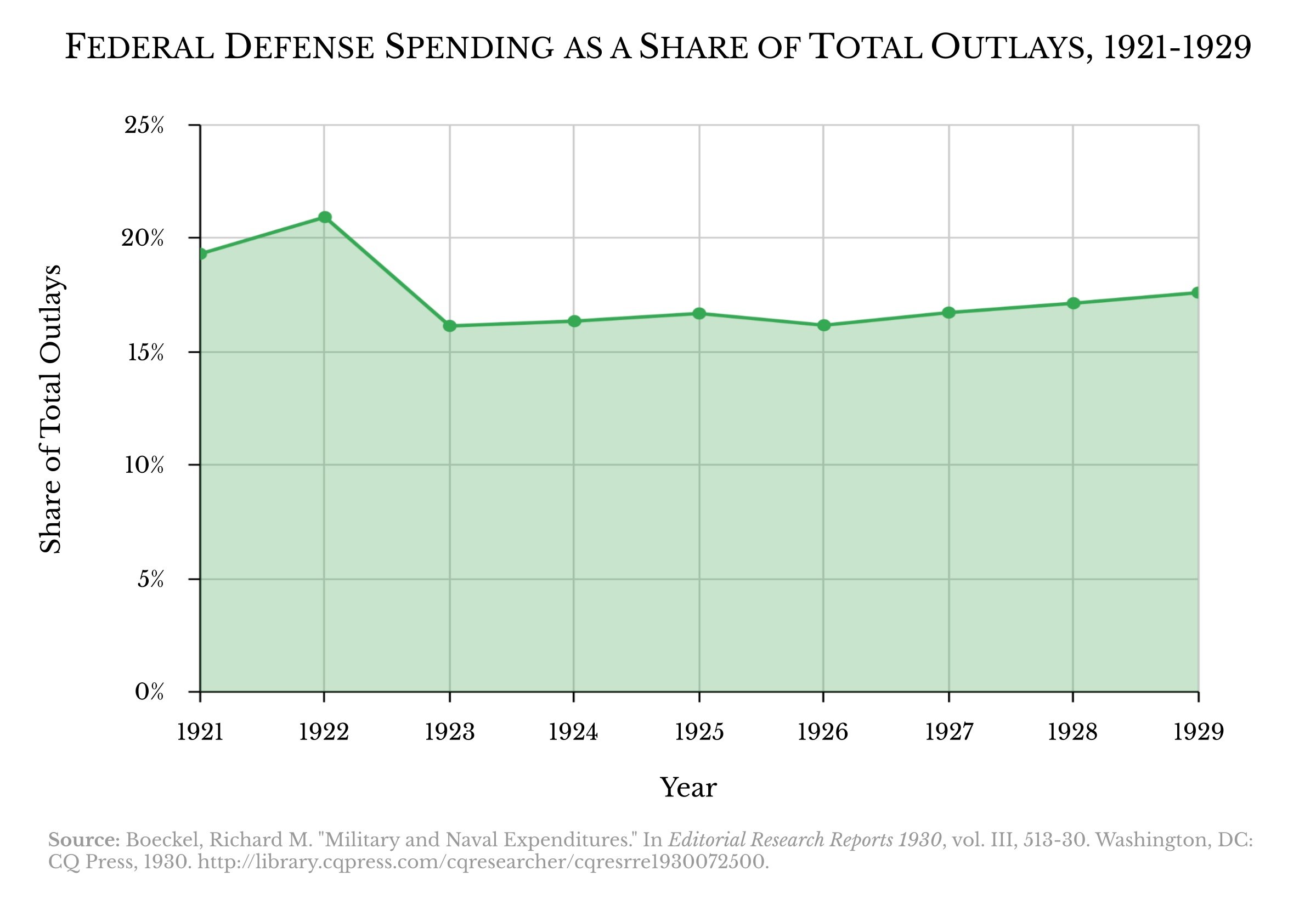

In Coolidge’s era, the biggest item in the budget pie was defense. How many warships should the Navy maintain? President Harding had successfully pushed Congress to move such spending towards peacetime levels. Coolidge could not cut much further without confronting the risk that America would not be ready when war came again.

Coolidge held the line. Under President Coolidge, defense spending stayed at more or less the same level from 1923 to 1927, rising slightly towards the end. Budget spending rose as a share of total outlays, but that was not a sign of weakness: rather, the defense share of the budget rose because Coolidge and Congress restrained other spending. It was not that Coolidge wanted a feeble America. He believed it was important that America’s armed forces be prepared. In an October, 1927, press conference, Coolidge stated that defense expenditures would increase “by quite a considerable sum” in 1928 and 1929 because of additions to the Navy and “the development of our air forces.” Still, though, Coolidge believed that the nation’s ultimate strength lay in its industrial might, its wealth, and its productive agriculture. The best thing a President could do for the cause of national defense was to pay down debt, giving the country borrowing power it would need if war should come.

XII. Using That Budget Law

American presidents sometimes ignore a law that is on the books. This was not the case with President Coolidge and the 1921 Budget and Accounting Act. “I regard a good budget as among the noblest monuments of virtue,” as he once said. Twice a year, Coolidge assembled government departments in a hall. There, Coolidge and his budget director exhorted their captive audience–in something like the manner of a high school pep rally–to save and monitor spending, right down to the amount of pencils they used. Crucial here were two figures to whom Coolidge also delegated: General Charles Dawes, who later became Coolidge’s vice president, and General Herbert Mayhew Lord.

XIII. Twinning: Tax Cuts and Budgets

Coolidge abhorred overtaxation, which he defined as “legalized larceny.” It was also immoral for the government to waste taxpayer money. So Coolidge and Mellon made it clear that a federal government that lowered tax rates must also keep spending down. In 1926, Coolidge and Mellon pushed through yet another tax cut, the Tax Act of 1926. This historic Act, which has long been studied by tax scholars and lawmakers, dropped the top tax rate to 25%, lower than even Ronald Reagan’s tax rate of 28%. But the moral point is important: only a consistent government can keep the public’s faith. Coolidge, therefore, only permitted himself to support tax cuts when he showed equivalent rigor in budgeting.

The White House made a point of this dual mandate when Coolidge received a pair of lion cubs as a gift from a mayor in South Africa. The White House named the cubs “Budget Bureau” and “Tax Reduction” as a symbol for the public.

XIV. An Abiding Challenge: Muscle Shoals

Throughout the 1920s, as the Great War moved into the distance, many lawmakers continued to devise new ways to widen the federal government’s role in the economy. One such plan was led by an eminent senator from Coolidge’s own party, George Norris of Nebraska. During World War I, the government had built a dam at Alabama’s Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River to generate power for war purposes. Norris and others wanted the government to keep the dam in peacetime and generate power for the people. Coolidge opposed such legislation, arguing the dam should be put in private hands–a deal for a takeover by Henry Ford was in the offing. The precedent of government in the power business was a poor one, Coolidge held. But the Ford deal never became law. And Norris and the idea of government power came back over and over again in Coolidge’s presidency. This was one contest that Coolidge lost, though after his death. In 1933 President Franklin Roosevelt used the dam as the basis for the government’s permanent move into the hydropower business by joining Congress to create the Tennessee Valley Authority.

XV. The Gift of Saturday

Today we often think of the 1920s in terms of The Great Gatsby, the book by F. Scott Fitzgerald: a decadent flash in the pan. But the Gatsby impression notwithstanding, the roar of the 1920s was real. Normalcy worked for regular Americans. The strong economy gave working Americans many freedoms they had not seen before: Model T cars, and then, Model As. Radios became commonplace. Household appliances such as washing machines, hair dryers, and toasters revolutionized home life and liberated homemakers, then nearly all women. In 1923, around 35 percent of homes had electricity. By 1929, more than two-thirds of Americans had electricity. Jobs, including those for veterans, proliferated. There was scant inflation and workers felt they had moved into a golden age with coins in their pockets and strong prospects for their careers. One way to understand the benefit of the 1920s growth is to think about the work week. Until the 1920s, the six-day work week was a rule. But new routines and machines made firms so productive that they could pay workers the same wages–or more–for fewer hours. That meant workers could take Saturday off, a new trend. Though Henry Ford only made the five-day week official in 1926, years before workers began to understand that productivity gains were making Saturday off a possibility. The prospect of that free Saturday, along with other improvements they were already enjoying, inspired voters to elect the nay-saying Coolidge in his own right–and in a landslide–in 1924.

Times Square in New York City circa 1920s. (AP Photo)

A busy drug store fountain in Southern California in 1927. (Alamy)

XVI. Supporting Charity

If the federal government wasn’t to supply daily needs of millions of citizens, then states, towns, and families must. And who would take care of the ill or the aged? In the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, town and state governments, and–this is key–community groups and private charities were the answer. Coolidge had grown up in, and saw value in preserving, the America of Alexis de Tocqueville, one led from the ground up.

Today we dismiss charity, especially, as a minor player. But to Coolidge, charity was central. A review of Coolidge’s calendar shows the effort this president put into praising and encouraging charity–and churches. In an era when progressivism was on the rise, when many policymakers were giving governments responsibilities that private communities had long handled, the President underscored that private groups, churches, should not easily cede their role. To the Holy Name Society, Coolidge stated that “the people of our country have secured the greatest success that was ever before experienced in human history.” That success was due to the local nature of American society and evidenced in “our wealth, our educational facilities, our charities, our religious institutions, and in the moral influence which we exert on the world.”

That however did not mean that charity could not rationalize or aggregate its activity. Coolidge detailed the reasons charity must work to function well, and how much he appreciated that work. In one of the nation’s first conference calls–telephones were still new in those days–the president reminded another such group that rational centralization and budgets were and should be everyone’s concern: “I dream of balance sheets,” the president confessed to the charity. But, moving beyond the goal of efficiency to the moral imperative of their cause. Coolidge praised the community for their devotion “to the ideal of taking care of their own.” He also praised the group for recognizing the responsibility of individuals and individual charities. “I want you to know I feel you are making good citizens.” This particular conference call was to Jewish philanthropists, but Coolidge exhorted other religious groups and local communities in the same way.

XVII. Living by Example

When a president gets into trouble in his personal life, he tends to lose voter faith, and the faith of lawmakers on Capitol Hill. Coolidge determined that his would be a pristine White House, so that there would be no distractions from his legislative goals. He was asking America to save money, so the White House must as well. The rigor was even applied to the White House dinner table. When the White House housekeeper, Elizabeth Jaffray, spent at specialty shops, Coolidge bridled. “Too many hams,” Coolidge commented, looking at one spread. Soon enough, the White House replaced Mrs. Jaffray with a new housekeeper, the more modest Ellen Riley. In 1927, for example, Miss Riley submitted documents that showed she had reduced the entertainment outlays to $9,116.39 from $11,667.10. That earned a rare note of praise from the laconic president: “very fine improvement.”

XVIII. The Achievement

Coolidge did what he promised. He always balanced the budget. Over the course of the 1920s, Harding, Coolidge, and their crucial ally, the Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, cut the federal debt by one-third. Indeed, Coolidge left office with a budget lower than when he took office, an achievement of great skill and perseverance given that America grew strongly in the 1920s.

Beyond these technical feats, Coolidge’s budget drive represented another achievement: the drive restored America's confidence in itself. Coolidge’s balanced budget was a national achievement, and restored citizens’ faith in their government. In his 1927 annual message, Coolidge pointed out that America’s budget integrity also increased the respect of other nations, a respect reflected in that most unforgiving metric, the interest rate. A balanced budget, he said, was “the corner stone of our national credit, the trifling price we pay to command the lowest rate of interest of any great power in the world.”

XIX. Threats to the Legacy

Coolidge himself saw that his successors would have more trouble holding the line. Thanks in good measure to him, prosperity had been the rule in the 1920s. But the stock market had risen so high that he himself knew it would crash one day. Markets periodically do. Then, tax revenues would disappoint.

Another challenge was emerging. By the end of the 1920s, voters had grown tired of being told that a deficit was a threat to the United States. Americans had enjoyed so many years of surplus that they no longer feared for their country.

By the late 1920s, new economists began to argue that deficits were acceptable and that more spending was, therefore, acceptable as well. This was an early version of the economic philosophy of Keynesianism. The Chamber of Commerce gave this notion a stage in 1927, calling a deficit “no great cause for alarm”–doubtless a provocation to the rigorous Coolidge.

In his last full year in office, 1928, President Coolidge also worried that the man emerging as his successor, Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, would not, if he became President, emphasize budgets as Coolidge had. Coolidge had always presented himself as a minimalist and a naysayer, in part because that made him harder to approach for spending. Hoover, by contrast, presented himself as a master of emergencies. That persona created a vulnerability in Hoover: politicians would more legitimately be able to demand that he act–and inevitably spend–in emergencies. Confiding to Secret Service man Edmund Starling, Coolidge said of Hoover: “well they are going to elect that superman Hoover, and he’s going to have some trouble. He’s going to have to spend money.” Coolidge’s prophecies came true: budgets grew after his presidency, especially after the historic stock market crash, and deficits became the rule.

THE COOLIDGE LEGACY

Some people blame Coolidge for the Great Depression, the deep downturn that endured through the 1930s. The facts however don’t bear out that conclusion. The Coolidge Foundation has devoted a special issue of the Coolidge Quarterly to the evidence on Coolidge and the Depression: for detail, that document is a good place to start. Whatever we think about the Great Depression, however, the Coolidge Legacy still warrants our study. Today we wish the government knew how to balance the budget. Studying Coolidge will help us to understand how that would be possible.

“I regard a good budget as among the noblest monuments of virtue.”

— “Discriminating Benevolence,” October 26, 1924.

“Thrift does not mean parsimony. It is not to be in any way identified with the miser…. In its essence it is self-control. Industry and judgment are required to achieve it. Contentment and economic freedom are its fruits.”

— Calvin Coolidge Says, January 17, 1931.

“I am for economy. After that I am for more economy.”

— “Address at the Seventh Regular Meeting of the Business Organization of the Government,” June 30, 1924.

“We must keep our budget balanced for each year. That is the corner stone of our national credit, the trifling price we pay to command the lowest rate of interest of any great power in the world. Any surplus can be applied to debt reduction, and debt reduction is tax reduction.”

— Messages and Papers of the Presidents, p. 9723.

“I began to take real interest, for the budget idea, I may admit, is a sort of obsession with me. I believe in budgets. I want other people to believe in them.”

— “Discriminating Benevolence,” October 26, 1924.

“I favor the policy of economy, not because I wish to save money, but because I wish to save people.”

— “Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1925.

This project is the work of Sam Williams, the 2021-2022 Coolidge Fellow. The Coolidge Foundation thanks Jerry Wallace, John Cogan, and Daniel Heil for their support and advice.